This is the abstract and tentative title for an accepted chapter in the forthcoming book, The Future of Surfing in the Anthropocene – Technology, Environment and Society

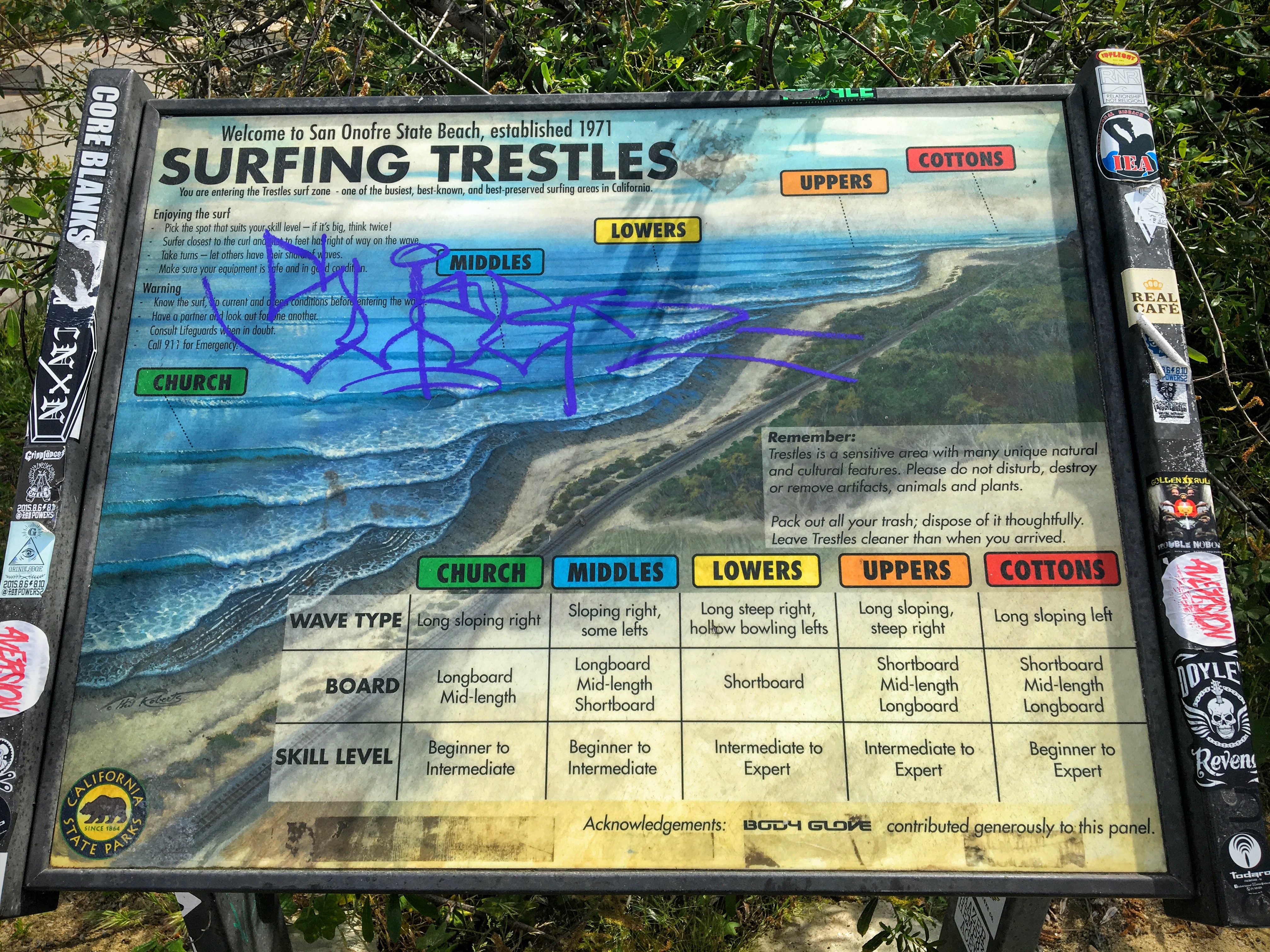

A growing number of citizen and community science initiatives aim to provide digitally democratic ways for surfers and non-scientists to document the impacts of sea level rise (SLR) at vulnerable surf breaks. In the case of University of Southern California Sea Grant’s citizen science project called the “Urban Tides Community Science Initiative,” three technological tools were central to SLR data collection efforts along Southern California’s coast in 2016. They included the volunteer’s smartphone, as well as an app and a cloud-based storage system designed by the now-defunct startup Liquid. Reflecting on my yearlong involvement in Urban Tides throughout 2016, this chapter identifies methodological challenges that arose when I used my smartphone to collect SLR data and synchronize it to Liquid’s server with the startup’s app. In documenting SLR conditions at Trestles in San Onofre State Beach during 2016 El Niño, synchronization issues ultimately rendered my data unusable for scientific analysis. I argue that being a community science ‘data bitch’ (Liboiron, 2017) for scientists and startups that are conducting SLR research on the Anthropocene Ocean can increase ocean and climate change literacy at personal and local levels. Cultivating private-public partnerships is also vital for advancing community science projects. Even so, academic institutions that collaborate with startups that provide a cloud-based storage system for valuable coastal data are engaging in a fraught process that can result in data extinction. How might traditional or alternative methods for documenting SLR ensure valuable community science data does not disappear? And what are potential best practices to consider for future community science projects that turn to surfers to collect SLR data? If such data is supposed to inform future coastal resilience and adaptation strategies, then it must be preserved and remain publicly accessible to communities even after the project concludes or the server and platform shut down. The erasure of public access to the 2016 Urban Tides data sets and the demise of the novel Liquid app reveals broader socio-technological implications for future community science projects that ask surfers to submit data about vulnerable surf breaks with a smartphone and app.